Cryptid Kitchen explains many aspects of flourishing. The content is grouped into topic areas. Knowledge nuggets about brain basics are in a mine.

The mine is pretty cool. Crystals, floating glittery things, nothing scary.

Our brains are complex meat machines. They’re sophisticated, but not perfect. Sometimes they do things we’d rather they didn’t. Like get depressed, or judge people too quickly.

Knowing how brains work can make you less anxious, more forgiving of yourself and others, and help you flourish more. That’s what Tiny Mining Town is about.

Like every area, the mine starts with a sign, introducing the topic, brain basics in this case. As you walk through the mine, you find brainy knowledge nuggets. It ends with a concluder, summarizing the topic.

Here are the knowledge nuggets at the time of writing. They’ve probably changed, though. Look in the game for the latest stuff.

Sign

Our brains are meat machines. Incredibly complex, not fully understood, but researchers have figured out some of how brains work.

A question. Why would knowing how brains work help you with flourishing?

Hmm… ’cause maybe… If I want my brain to do something, and I know how it works, maybe I can figure out how to get my brain to do what I want?

Hmm… ’cause maybe… If I want my brain to do something, and I know how it works, maybe I can figure out how to get my brain to do what I want?Good thinking! You’re right. For example, since we know something about how brains learn, we can work out how effective different study methods will be for us. Tiny Christmas Town is all about that. It gives you six learning methods that work, so you can use your learning time efficiently.

Another thing. Sometimes our brains automatically do things we’d rather they didn’t. Like get depressed, or judge people too quickly. If we know about those things, maybe we can make adjustments.

Knowing how brains work can make you less anxious, more forgiving of yourself and others, and help you flourish more. That’s what Tiny Mining Town is about.

Uses

Suppose Jimbo plays a prank on you. You’re gardening, and Jimbo wiggles a hose. You jump up. Jimbo laughs at you. “Scaredy cat! You’re like a cat with a cucumber! HAHAHA!”

Hey, back it up, bro! That’s the way our brains are wired! It’s like… OK, pick up a garden tool, and let go. Of course it’s gonna fall to the ground. What, are you gonna make fun of the tool, for being clumsy? Besides, cats are cooler than you’ll ever be.

Hey, that’s a good one! Anyway, either Jimbo doesn’t know much about brains, or he’s trying to manipulate you, consciously, or unconsciously. No reason to take what he said seriously.

Automatic

Most things you do, you don’t have to think much. Like walking. You don’t pay attention to each muscle. Your brain handles the deets.

Or gaming. When you’re learning, you pay attention to everything you do, like if a monster is chasing you, and you get stuck on a rock or something, jump to get free, and keep running. After a while, your brain learns to do it without conscious thought. Get stuck, jump. Get stuck, jump. Your brain just does it.

These are called automatic processes. You can do them without conscious attention. You can do other things at the same time, since the load on your brain is low.

This works well. Usually. Except when your unconscious reacts in ways you’d rather it didn’t. Suppose you’re playing a new game, where a flying monster can’t get you unless you jump. Argh! Your automatic think meat keeps jumping you into the path of the beast!

Sometimes it’s obvious when an automatic process needs to change. The jump-into-the-path-of-the-flying-beast example is like that. Your character keeps getting hit.

Other times, it’s not so obvious that your automatic processes aren’t helping you. For example, when you grew up, maybe you learned from your parents how couples interact. Not consciously, but you learned, nonetheless. You’ll carry some of your parent’s behavior into your own relationships, even behavior that doesn’t help.

As you explore the island, you’ll see this problem again and again: your brain does things automatically, that you’d rather it didn’t.

Uses

Next time you’re upset, ask yourself why. Suppose you spill some water at dinner, and you automatically say to yourself, “Self, that was stupid.” Umm… really? Spilling water makes you stupid? Wow, Einstein must have been a moron! He had trouble tying his shoes, and I bet he spilled water in his life, maybe more than once! What a loser!

See if you can identify some automatic beliefs and behaviors. Most help you. Some don’t.

You can reprogram your unconscious to some extent. The key is watching what your automatic self does. Then interrupt it. You can’t interrupt what you’re not aware of, so being aware of your automatic stuff is a Big Deal.

Attention

Look around you. How many things can you see? Hundreds?

Your brain gets tons of input, but you can only think about a few things at a time. How does your head meat stop from getting flooded?

It has two tricks. The first is attention. You can focus on a small part of your sensory world at one time. If a thing you’re focusing on changes, like it moves, or changes color, or speaks, you’ll notice. But you can’t pay attention to many things at one time, and might not notice other things that are happening.

The second trick is automaticity (it is too a word!). Your unconscious scans for special inputs. Like at a party, you’re talking to Jo, not paying much attention to anything else. Someone across the room says your name. Your brain pulls your attention to whoever said your name. Your automatic self pulls your attention to the Important Thing, even if you weren’t focusing on that thing a moment ago.

OK, but how does our subconscious know what to automatically scan for, when I’m paying attention to something else?

OK, but how does our subconscious know what to automatically scan for, when I’m paying attention to something else?Good question! Some things are kinda built-in, already wired up when we’re born. Like, things that are moving around grab attention. Or loud noises.

Other times, your brain has to program its unconscious, to know what the Important Things are. Your name is a no-brainer (see what I did there?). Or… maybe the sound of barking dogs is an Important Thing, if you love dogs, like all Good Humans do.

OK, so your brain has limited attention power, plus a there’s-an-Important-Thing system to switch attention around automatically. So – (drum roll please) – everyone misses most of what happens. If your attention is full, you won’t notice other stuff, unless they’re Important Things already programmed into your unconscious.

BTW, if you’re thinking deeply about something, you might notice even less about what’s happening around you. Your brain power is being used up. Strong emotions reduce brain power as well.

Fatigue plays a part as well. If you’ve been doing heavy brain work for a while, your Focus Juice gets all used up. You might not notice something you would have, if you’d been rested.

Uses

Say you get a new haircut. You really like how it makes you look. Your partner doesn’t notice. You say to yourself, “They don’t care about me!” Wadya think, Mothman?

I might be a little upset that they didn’t notice, but that’s not really on them. They probably have their own stuff going on, and have the same blind spots I do, especially if they’re stressed. Plus, if they’re someone I care about, I would want to give them the benefit of the doubt. There’s no reason to go looking for a fight!

I might be a little upset that they didn’t notice, but that’s not really on them. They probably have their own stuff going on, and have the same blind spots I do, especially if they’re stressed. Plus, if they’re someone I care about, I would want to give them the benefit of the doubt. There’s no reason to go looking for a fight!Right. Grab their attention. “Hey, honey! Check out my fierce ‘do!”

Another Useful Thing. You can use attention to resist temptation. Suppose there’s a marshmallow in front of you. You can eat it now, or, if you wait a few minutes, you get two. You want the two, but your unconscious is screaming, “Eat the marshmallow! Now!” (This was a real psychology experiment. You can google it.)

Move your eyes off the marshmallow. Look at other things in the room. Think about them. “How was that lamp made? Where does the electricity it uses come from? How many miles of copper wire were needed?” What you’re doing is burning up your brain power on unmarshmallowy things, leaving less for marshmallowy thoughts.

Memory

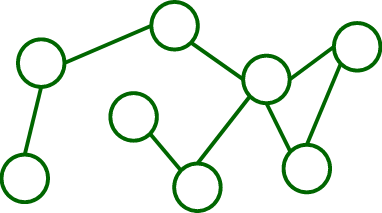

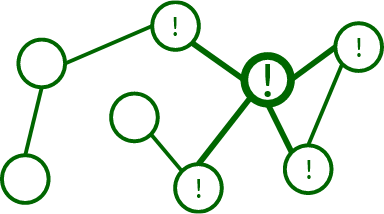

Memory is like a network.

When you recall one memory, similar memories get triggered as well.

Strong memories have thick connections to lots of other memories.

Memories come from what you’ve seen, and heard. We all see and hear different things. So, everyone has a different set of memories.

Memory for an event, like a birthday party, isn’t like a movie, recording what happened. It couldn’t be. Why not?

Er… Ooo! The attention nugget said we can’t pay attention to everything. Like, if we didn’t pay attention to the lamp on a side table, we won’t have a clear memory of it.

Er… Ooo! The attention nugget said we can’t pay attention to everything. Like, if we didn’t pay attention to the lamp on a side table, we won’t have a clear memory of it.Right. Memories for events are reconstructed from the things you paid attention to, and your memory meat stored. It might look like a movie in your head, but it isn’t. Making it seem real is a trick of our memory meat.

Scientists think every memory you have, every object you can name, has an emotional tag attached to it. Like the tags websites use.

Things tagged with bad emotions (like fear) are attention grabbers, more than things with good emotions (like joy). The stronger the emotion, the more they grab attention, and the stronger the memory.

Uses

People have different memories of the same event. Like, parents remember a vacation one way, their children another. Different things grabbed their attention, so their memory meat stored different fragments of the event.

When people disagree about an event, it’s usually because of how memory works, not because they’re trying to trick each other. Even vivid memories are reconstructions.

Memories of bad things are strong. That’s where PTSD comes from. The BOOM of a firework automatically triggers a memory of the BOOM of a gun. Connected memories, maybe of pain, and fear, jump in as well.

Someone with PTSD isn’t “weak.” It’s just how human brains work.

Emotion

Emotion is your primary decision maker. That’s what emotions are for, helping you make choices.

Wait, what?

Wait, what?We evolved on the plains of Africa. There were leopards, fruit trees, poisonous snakes, antelopes, much else. We made choices to survive.

People who saw leopards and started running, survived to have more kids, than people who sat for a while, wondering what the spotty animal with sharp teeth and claws was doing. Fast emotions lead to quick decisions that help survival.

There has to be a mechanism, linking see-a-leopard to run-away-fast. Emotions tie them together. Senses (see-a-leopard) to emotion (argh-that’s-scary) to action (run-away-fast).

Hmm. I read somewhere that we remember bad things better than good things. Are our brains that way because of evolution?

Hmm. I read somewhere that we remember bad things better than good things. Are our brains that way because of evolution?Good thinking!

Over and over again, psychologists find that the human mind reacts to bad things more quickly, strongly, and persistently than to equivalent good things.

Haidt, The Happiness Hypothesis, page 29, Kindle edition

Remembering where the leopards are, and where the fruit trees are, both help you stay alive. But remembering where the leopards are is more important. Oh, so that’s why memories have good/bad tags, like the memory nugget said! See something, if you have a memory for it, check out its tag, for a quick 4F decision.

Oh, so that’s why memories have good/bad tags, like the memory nugget said! See something, if you have a memory for it, check out its tag, for a quick 4F decision.4F?

Yeah, four basic behaviors: feed, fight, flee, and mate.

Yeah, four basic behaviors: feed, fight, flee, and mate.Ha! I like it.

There’s another way to make decisions: thinking things through. You look at the evidence, and choose. Slower, but sometimes gets better results.

Why would it get better results? Every memory has a good/bad tag, so you just look at those.

Why would it get better results? Every memory has a good/bad tag, so you just look at those.Where do those tags come from?

Hmm… what you were feeling when you made the memory?

Hmm… what you were feeling when you made the memory?Say you saw a mango tree (yum!). As you got close, you heard a hiss, and saw a big snake. Argh! Your memory of mango trees could get a “fear” tag.

I get it! You see mango trees later, somewhere else, and you feel fear, even though there are no snakes.

I get it! You see mango trees later, somewhere else, and you feel fear, even though there are no snakes.Yes! We have a thinker, though, a thinking-things-through system. It might be able to override the automatic fear.

Like, when you see other people going to the new trees, your thinker might start questioning the automatic fear. When people you trust tell you there are no snakes, and mango is the Best Fruit Ever (which it is), your thinker might be able to override the fear. Over time, the fear memory will lose strength.

Most of your decisions are made by your automatics, guided by emotion. Usually that’s just fine. Sometimes, you can use your thinker to change things. Especially when your thinker has evidence, like what other people do and say.

Another thing. You often use your thinker to serve your emotions, to get the decisions your tags want.

So… emotions drag thinkers along?

So… emotions drag thinkers along?Yes, and even make them change memory tags. For example, political beliefs have good/bad tags. Say you think gun control is a Good Thing. You move to a new town, and you want to make new friends. Social approval is a Great Big Thing to people, one of the most powerful reasons people do things.

Most people in your new town think gun control is a Bad Thing. You really really really want people to like you. Your thinker can use its reasoning power, to justify changing your good/bad tag for gun control. You say to yourself, “Well, when you think about it, (insert argument here).” Now it’s easier to make new friends.

The thinker helps your feeler get what it wants.

(We’ll talk about social effects in other Tiny Towns. Spoiler: they’re very important.)

One problem is that thinkers don’t always know why feelers feel what they do. You can be afraid, and not know why.

Feelers evolved first. Lotsa mammals have them. Thinkers are kinda layered on top, but not fully wired up to feelers. Some scientists believe thinkers do a lotta guess work, by looking at what feelers are doing to our bodies.

Part of your feeler system, a meat blob called your amygdala, scans what you see and hear. When it detects something that might be a threat, it starts your emotions running. It doesn’t check with your thinker, to see if the emotions make sense. It just pulls the emotional trigger.

So, your emotions start without your thinker being involved. Your thinker knows something is going on, but not what. It’ll check out your visual memory, and what you heard, smelled and touched. It usually figures things out, but it can be wrong. Thinkers are often sure they’re right in these situations, but they might not be.

You’ll learn about the effects of the feeler-thinker disconnect as you wander the island. For example, Sarah asks Bill why he’s depressed. He says, “I don’t know.” Sarah says, “Come on, you must know.” She’s wrong. Bill’s just being honest.

One last thing. People have happiness set points, their default level of happiness. When something good or bad happens, they jump away from their set points, but eventually, they return. People who win the lottery are thrilled for a while, but they get back to their set points after a bit.

Getting more stuff won’t necessarily make you happier in the long run. It gives you a short-term boost, but you get back to your set point quickly. Turns out, experiences have a more lasting effect on happiness than things. In general, going on an overseas vacation will have a more lasting effect than getting a new car. Still, don’t expect a permanent change in your happiness.

Uses

The Sarah and Bill thing is important, especially in relationships. People are usually sure they know what’s going on in their world, but it’s easy to be wrong, especially when it comes to other people. Maybe Sarah thinks Bill is hiding something. (He isn’t; it’s just the way brains work.) She badgers Bill, and distrusts him. He learns to hide his emotions from Sarah. They pull away from each other.

OK, no big deal, they don’t get along. But what if they’re married? What if they have kids? Yeah, then it’s a Big Deal.

This brain, flourishing stuff. Learning about it is a good idea.

This brain, flourishing stuff. Learning about it is a good idea.When you’re making a decision, ask yourself why you believe what you do. Or do that right now. Pick something with a good/bad tag, and ask yourself where the tag came from.

You do that with other people, too. If someone else believes something you think doesn’t make sense, you might ask yourself why they think that. And why you think it doesn’t make sense.

You can change your good/bad tags, with your thinker. Suppose you grew up among racists, and absorbed the belief “Blacks are bad.” Your thinker can challenge your good/bad tag, by looking at the evidence. (Check out Diamond’s book, “Guns, Germs, and Steel” for some cool history on cultural differences.)

For that to happen, first you have to notice your belief. That’s tricky, since, when your memory meat thinks about something, its tag is fetched automatically. You have to pay attention to your thinking, if you want to become aware of beliefs that aren’t serving you well.

A warning, though. Questioning yourself can make you feel bad about yourself. Questioning others can make them angry at you.

Yeah. But, if you have a belief you think is wrong, that doesn’t make you evil, or anything.

Yeah. But, if you have a belief you think is wrong, that doesn’t make you evil, or anything.Good point. You don’t get to choose how your head meat works. It’s wired up in a certain way, and that’s that. The best you can do is become aware of the wiring, and move things around a little.

You can work on changing beliefs. The key is to be aware of them. More on that later.

Take it easy on yourself, and on others. Get some mango. Play with your dog. Dogs make everything better.

Thought

Your head meat has a feeler (fast emotional good/bad decisions), and a separate thinker (slower, conscious). For realsies, your feeler and thinker work together. (Some scientists believe thinkers can’t make choices at all without feelers.) Keeping feeler and thinker separate makes it easier to explain things, so let’s stick with it.

Both feelers and thinkers are deciders. Leopard -> run away, mango -> eat it, Susan from HR -> hide. Your feeler evolved first, and is the only decider for most mammals. Thinkers came later, to improve on what feelers were doing.

How do thinkers improve on feelers?

The [thinker] allows people to think about long-term goals and thereby escape the tyranny of the here-and-now, the automatic triggering of temptation by the sight of tempting objects. People can imagine alternatives that are not visually present…

Haidt, The Happiness Hypothesis, page 17, Kindle edition

“The tyranny of the here-and-now.” Even if something has a good tag (on the good/bad scale), the thinker can say, “No, let’s not do that right now, so we can do something better later.” Thinkers can predict, and plan.

It doesn’t go too far, though. The feeler has more control over behavior than the thinker. The thinker is an advisor to the feeler, not the boss.

Language is the thinker’s superpower. We think to ourselves in language. We talk to other people in our heads, to think things through.

Language gives us access to other people’s thinkers. That’s a megapower. Civilization wouldn’t exist if humans couldn’t build on each other’s knowledge.

One last thing. Brains are inference machines, that is, they jump from a visual input to an assumption, to another assumption, to another, and so on. It’s fast, and automatic. Here’s a (very) short story:

Mom said, “Hey, can you get the door? The pizza’s here!”

Picture the scene in your head. Did you add a doorbell sound? That’s not in the story. Did you add a pizza delivery person? Not in the story, either. Money? Not there. A house, or apartment? Not there. Dad, kids? There’s only one person in the story.

“Get the door” doesn’t mean “go bring the door here.”

“Get the door” doesn’t mean “go bring the door here.”Your brain inferred all the stuff that wasn’t there, based on your knowledge of pizza delivery situations. You filled in the missing details. You did it fast, and automatically. If someone asked you what the story said, you might say:

There was this family, they ordered pizza, and a guy delivered it.

Not what the story said, but it’s what you imagined.

Uses

Your thinker can influence your feeler. A bit. Sights (a cake), sounds (“Get your cake here!”), scents (cake!), automatically trigger memories with good/bad tags. Your feeler shouts, “Me eat cake!” Your thinker is a little voice in the background, easy to ignore. So, nom nom that cake.

Your thinker can change your environment, so your feeler doesn’t get triggered, or isn’t as strong when it is triggered. Don’t have pictures of cakes lying around. Eat before you go to the supermarket. You’ll see cakes there, but the feeler will be less powerful, because you aren’t hungry.

Your thinker can even get your feeler to fight itself. OK, so your feeler wants that snack in the fridge. It also wants you to be popular. You could tape a picture of happy thin people on the fridge, where your feeler has to see it. Sneaky, right?

You could be really mean about it, too. Bad feelings are stronger than good. Make it a photo of thin people laughing at fatter people.

You could be really mean about it, too. Bad feelings are stronger than good. Make it a photo of thin people laughing at fatter people.Yes, that might work in the short term, but it reinforces a bad self-image, too. That might backfire in the long run. But 10/10 for understanding head meat.

One last use. You can mislead people, using their automatic inference. Advertisers do this. “The [thing] more hospitals use.” The natural inference is the thing must be better than other things of its kind. But maybe the manufacturer sells the thing really cheaply to hospitals. And “more hospitals use…” than what? How is it counted? Total number of things? Total number of hospitals? All hospitals, or just some?

It makes you think.

Body

Oh, man, I hate exercise. Like, I do it, but it isn’t fun.

Oh, man, I hate exercise. Like, I do it, but it isn’t fun. Wait, what?! Exercise helps you think better?

Wait, what?! Exercise helps you think better? What’s going on, exactly? Exercise makes you thin, and thin people live longer? Is that it? A lotta people think that.

What’s going on, exactly? Exercise makes you thin, and thin people live longer? Is that it? A lotta people think that. Huh. So, exercise is what really matters?

Huh. So, exercise is what really matters?Yes, it looks that way, for longevity, and better brain function.

Socially, it’s different. Most people think Thin is Good, but Fat is Bad. Losing weight will make those people think better of you. Kinda shallow, but that’s humans for you.Evolution

Evolution affected our brains, as well as our bodies. Evolutionary psychology studies how evolution changed our feelers, and thinkers.

For example, humans are the most social species we know about. One part of that: we care what others think of us. Like, really really care, a lot a lot.

Why?

Here’s one theory. We came out of Africa about 60,000 years ago. A while before that, maybe 80,000 to 100,000 years ago, there was a long drought in Africa, decades long. A buncha species died out, and we almost did, too. Our numbers got lower than they’ve ever been.

So, which humans survived, and could pass on their genes?

I’m thinking it was the big, tough guys. They could steal everyone’s food.

I’m thinking it was the big, tough guys. They could steal everyone’s food.Another thing. Humans were hunters and gatherers. Hunting was an iffy thing. You get an antelope one day, then nothing for three days, then another antelope, then nothing. Gathering was more reliable, mostly, but still, some days would be better than others. The village got the best results if they shared their food with each other.

There were other benefits to cooperation. Say Og made really good spears. Hunting parties were more successful with Og’s spears. It would make sense for Og to stay in the village, making spears. Although Og didn’t hunt or gather, the village was better off.

Huh. OK, so, almost all the humans died. The ones who survived, were the best at working together?

Huh. OK, so, almost all the humans died. The ones who survived, were the best at working together? Oh, yeah, there are people at work like that. We make sure everyone knows who they are. You don’t want them on your team.

Oh, yeah, there are people at work like that. We make sure everyone knows who they are. You don’t want them on your team.Yeah, Og’s good, love her spears, but Kwocko, he just lays about all day, scratching himself.

Your reputation was very important. If people thought you enough of a loser, they’d kick you out of the village. That was a death sentence. Long drought, remember, and hungry leopards.

OK, here’s the kicker, and why this matters. You can see how evolution would have favored certain traits among our ancestors, like sociability. Does that make sense?

Yeah, I can see that.

Yeah, I can see that. Oh, d00d, that’s lit! They were running around in Africa, chasing antelopes, avoiding leopards, in a long drought. We’re living in cities, hanging out in coffee shops. Internet trolls, not leopards! But our brains suit the ancient environment, not our modern one.

Oh, d00d, that’s lit! They were running around in Africa, chasing antelopes, avoiding leopards, in a long drought. We’re living in cities, hanging out in coffee shops. Internet trolls, not leopards! But our brains suit the ancient environment, not our modern one.An example of that is in our food. Take sugar. Many calories, an energy boost for hunting. Makes sense for our ancestors to like sugar, a lot. Back then, there wasn’t much of it. Honey in hives, maybe a bit in tubers, but that’s about it. So, liking sugar helped people survive back then, with no downside.

Now, sugar is easy to get, but our bodies still like it. Nom nom NOM! Our love for sugar, useful in the ancestral environment, causes health problems today.

Back to the social stuff. In the ancestral environment, when someone dissed you, it mattered. Villages were small, too, maybe 100 people, so everyone would know about it. That would after how much food you got, how much sex, and other things.

Fast forward to now. Someone leaves a nasty comment on your TikTok. So what? There’s 7+ billion people. Even if thousands of people think less of you because of the comment, it’s unlikely you’ll know any of them. It has zero effect on how much food and sex you get.

But it feels awful! Your feeler is programmed with rules from long ago, even if they don’t fit today.

But it feels awful! Your feeler is programmed with rules from long ago, even if they don’t fit today. Can your thinker argue with your feeler about this?

Can your thinker argue with your feeler about this?Having your thinker intervene works for some people, but not others. Don’t give up. The more your thinker argues, the stronger it gets.

Concluder

The nuggets in this mine are about how your brain works. The thing you think of as “you” is a result of what your head meat does.

Sometimes, the way brains work gets in the way of flourishing. For example, you get annoyed when a “friend” walks by without saying hello. You might think, “Well, she’s no friend of mine.”

That’s a mistake. Maybe her brain was full, with no attention left. She might not have noticed you. Not everything’s about you, even though your threat-watching brain thinks it is.

Give her a break. Give yourself a break, when you make a mistake. Maybe it’s just because of how the meat in your head fumbles through the day.

There’s lots more to say about your brain. You’ll learn more about it in other parts of the island.