Cryptid Kitchen explains many aspects of flourishing. The content is grouped into topic areas. Knowledge nuggets about learning are in Tiny Christmas Town.

Like every area, it starts with a sign, introducing the topic. As you walk through the area, you find knowledge nuggets. It ends with a concluder, summarizing the topic.

Here are the knowledge nuggets at the time of writing. They’ve probably changed, though. Look in the game for the latest stuff.

Learning helps you flourish. Accomplish things, earn more, get better at stuff that’s meaningful to you, feel good about what you can do.

Most people are teachers, as well as students. You help your friends, children, people at work… Even if you’re not a full-time teacher, you teach.

Learning takes effort. This tiny town has ways to make learning more efficient, and effective. There are six practices, all backed by research.

Do you suck at learning?

No. If you can read these words, you don’t suck at learning.

Learning is one of our species’ survival strategies. Unlike other animals, we can’t do much when we’re born. In prehistory, we’d learn to hunt, gather, farm, herd, whatever, from our parents, and others in the tribe. The specifics – like how to hunt – would depend on where we lived. Hunting in the jungle, and hunting on an ocean shore, are different.

So, why would people think they’re bad at learning? A few reasons. One is that some teachers and courses suck. I’ve bought a coupla dozen cheap online tech courses over the years, and a few more expensive courses. I’ve never found one that I would call good.

Why? First, know that my standards are higher than most people’s. I spent a long time studying research on how people learn, and how we can help them learn. I’m able to make good online courses because I know what helps learning, and what gets in the way.

People who’ve made the online tech courses I’ve seen haven’t studied learning. They’re programmers, designers, whatevs. Teaching is a different skill from programming. One is about computers, one about brains. Unless you study both, making a good online course is a matter of luck, not skill.

Another reason people might think they suck at learning is they’re never learned how to learn. Like, reading a textbook again and again and again isn’t a good way to learn.

Yet another reason is that knowledge is cumulative. It’s hard to learn programming if you don’t know basic algebra. Like working out how many dozen eggs you need if you need 24 eggs. (It’s two.) There are things you need to know before you start a course, if you’re going to be successful.

Another reason people think they suck at learning, is they watch someone on YouTube explaining how to do something, and because it seems so easy for the YouTuber, they think it’ll be easy for them, too. They try it themselves, and fail. Then they think,

“Wow, I suck! That looked so easy.”

Just because something looks easy on YouTube, doesn’t mean it is. Experts spend many hours practicing the moon walk, or whatever it is. Brains need that practice to learn.

Also, remember you’re only seeing the expert’s successes. The expert makeup artist? She messed up three times, before she got the look right. The mistakes aren’t on the video.

It’s easy to get discouraged when learning. You don’t understand some things at the beginning of a course. You don’t understand the next things that rely on knowing the first things. The whole thing gets too hard, and you give up.

This tiny town is about the basics of how to learn. Find a good course, use these techniques, find someone patient to help, and you’ll be OK. Your brain has evolved to do this learning thing.

Close your biology textbook. Now explain mitosis to your dog. A person if there’s one willing, but your dog works, too. Explaining brings the knowledge to mind, in a different form than the reading you did. Also, when you explain something to someone, you have to fill in gaps in your knowledge, that you didn’t know were even there.

Ask yourself questions, too. “Self, what does it mean that….” I used to do that all the time when I was a student.

I draw a face on my thumb, and explain to that. I call it Jacko.

I draw a face on my thumb, and explain to that. I call it Jacko.Retrieval practice is El Jefe of these learning tips. If you do only one, do this one. Though I don’t know why you would do just one.

Retrieval practice is about purposely remembering something after you’ve learned it. It’s best if you do it a bit after you’re learned, so you have a chance to start forgetting. Also, retrieve in a different form than you learned it in.

Abstract ideas are often hard to grasp.

What does “abstract” actually mean?

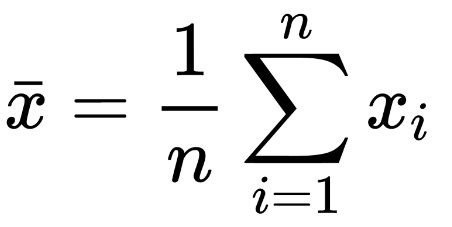

What does “abstract” actually mean?Take averages. Here are concrete examples.

The average of 2 and 3 is 2.5.

The average of 2 and 4 is 3.

The average of 10 and 20 is 15.

They all have the same template:

The average of x and y is (x + y)/2.

OK, a template with slots. Fill in the slots to get something concrete.

OK, a template with slots. Fill in the slots to get something concrete.An even more abstract version lets you have not just two numbers, but any number of numbers.

Argh! My eyes! My eyes! You’re burning them!

Argh! My eyes! My eyes! You’re burning them!If you’re teaching, start with concrete examples. Show how you can turn specific values in the examples (like 2 and 3) into slots (like x and y). Build a chain in students’ heads, from concrete to abstract.

If you’re learning, ask for concrete instances. Look at several. See what values they have in common, that you can change into slots.

Your brain can use different types of information. Verbal and visual information, for example.

Dual coding is when you have visual and verbal info about the same thing. Both of them combine to give you a stronger memory about the thing, than either one would give separately.

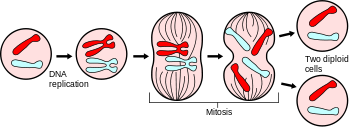

This is from Wikipedia:

In cell biology, mitosis (/maɪˈtoʊsɪs/) is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is maintained.

Here’s another explanation:

You get a stronger memory for mitosis if you get both descriptions, instead of one or the other.

When you’re teaching, give students both text and images of the same idea. When you’re learning, it helps to draw a picture of what you’re reading (or a description of a drawing).

In our head meat, the better connected a memory is to other memories, the stronger the memory will be. Elaboration is about this. It adds details to an explanation, building more links.

Elaborative interrogation is one version. You ask yourself questions, like how something works, why it works that way, when does it happen, and what causes it. All of the memories reference each other, making them all stronger. (There’s a related method called retrieval practice, somewhere around here.)

For example, you want to remember pi is an irrational number. You could ask yourself:

- What is pi?

- What can you do with pi?

- What’s an irrational number?

- Why are they called irrational? Are they crazy?

- Is it irrational to like pumpkin pie? What about shepherd’s pie?

All of these things create links to what you want to remember.

Switch from learning one thing to another, rather than studying the same thing for a long time.

Say you’re learning basic algebra. You have, say, sixteen practice problems. There are four topics: linear equations (L), inequalities (I), factoring (F), and exponents (E). You could do all the problems about one topic, all the problems about the next, etc. Like this:

LLLLIIIIFFFFEEEE

That’s called blocked practice, and is what most people default to.

Or you do them in random order, like:

LFIEFLIILEFEFILE

If you do blocked, you’ll feel better about your learning than if you did random. But random is actually more effective.

Huh?

Huh? Ooooh. So you get most the learning value from the first one, not the rest. It’s like you’ve done one full problem, and then a bunch of problem fragments.

Ooooh. So you get most the learning value from the first one, not the rest. It’s like you’ve done one full problem, and then a bunch of problem fragments. Not as good, maybe? Every problem takes the remember-how-to-do-it effort. You don’t get the this-is-easy feeling, as least not as much.

Not as good, maybe? Every problem takes the remember-how-to-do-it effort. You don’t get the this-is-easy feeling, as least not as much.The next bit is the pay dirt:Spaced practice is the exact opposite of cramming. When you cram, you study for a long, intense period of time close to an exam. When you space your learning, you take that same amount of study time, and spread it out across a much longer period of time.

Notice: the same amount of study time gets you better results if you spread the time out. Finding more time can be hard. So, use the time you have well. Bee Tee Dubs, The Learning Scientists is my fave place to learn about learning.Doing it this way, that same amount of study time will produce more long-lasting learning.

Learning helps you flourish. Accomplish things, earn more, get better at stuff that’s meaningful to you, feel good about what you can do.

Most people are teachers, as well as students. You help your friends, children, people at work… Even if you’re not a full-time teacher, you teach.

Learning takes time. This tiny town has ways to make learning more efficient, and effective. “Efficient” means using your time well. Twenty minutes with retrieval practice can be worth more than an hour spent reading and rereading.

The tips are from The Learning Scientists, my fave place to learn about learning. Some tips have been modified a little. The tips are:

- Retrieval practice – Explain to your dog. Or Matcha. She’ll listen.

- Spacing – Spread study out over time. No cramming!

- Elaboration – Add details to the main ideas, to make them more memorable.

- Interleaving – Mix it up. Study a bit of this, then a bit of that.

- Concrete examples – Abstract ideas are easier to understand with a few examples.

- Dual coding – Pictures and words for the same ideas.

All of these things have scientific support.